In Zhang Yimou’s The Great Wall, Matt Damon plays a European mercenary who helps the builders of The Great Wall of China fight off monsters. Thus, it combines one of China’s favorite past times (monster movies) with one of America’s (cultural imperialism). Those two things don’t go well together. Not surprisingly, the result is a thoroughly mediocre movie which didn’t entirely please Chinese audiences in December and isn’t doing much better with American audiences this weekend. However, we’ve both rejected it for very different reasons:

Chinese audiences were more concerned with The Great Wall’s failings as a movie, finding flaws in Yimou’s directing and the performances of several of the young Asian actors.

We, on the other hand, can’t stop joking about the cultural insensitivity of having Matt Damon save Asians.

Doesn’t that seem a little backward? Isn’t it the actual people of China who should be registering their offense (or lack thereof) with this movie, not us?

Here’s how it went down from our end of things:

The first Great Wall trailer premiered in July.

Constance Wu was seriously displeased.

Matt Damon and Yimou repeatedly defended themselves in the press, fighting back against those accusing them of whitewashing since this isn’t a case of an Asian character being played by a white actor. No, it’s just a white character being written into an Asian story to make a rather expensive movie, the most expensive in China’s history in fact, more palatable to American and European audiences.

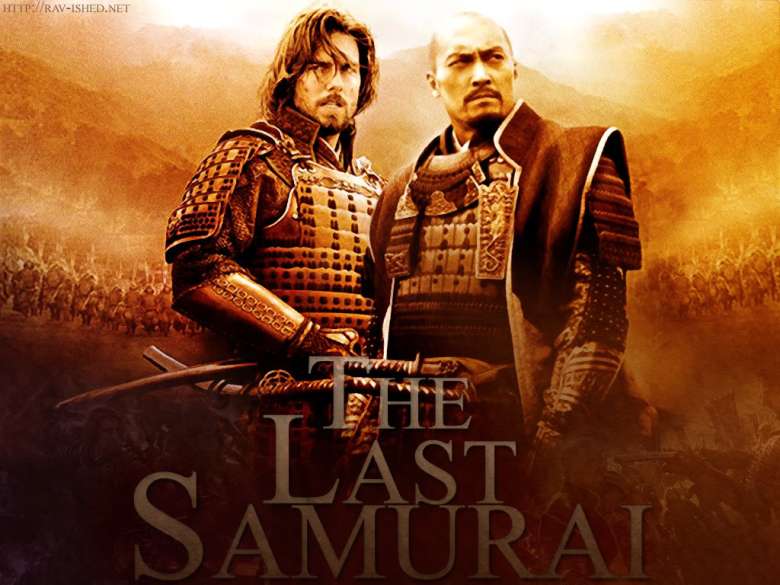

So, let’s get it straight: Scarlett Johansson playing an anime character in Ghost in the Shell is absolutely whitewashing; Matt Damon popping up in a monster movie set in Ancient China is white-savior syndrome at work. See also: The Last Samurai. As Vanilla Ice might say, “It’s not the same.”

Except it feels the same, and offends us almost equally. Because. This. Shit. Keeps. Happening.

There could soon come a time where US-China co-productions are the norm (Legendary/Universal kicked in on Great Wall) and the peculiar sight of American movie stars being shoved into films they have no business being in barely elicits much of a response. If that happens, though, it won’t entirely be due to Great Wall, which is not quite the box office hit it was meant to be. To date, it’s made $170m in China, and has an additional $54m in the bank from other foreign territories. However, it is headed for a disappointing domestic box office run, meaning it might fail to double its production budget ($150m) in worldwide gross. Plus, while that $170m in China might look impressive it’s not as high as it should have been considering the far cheaper ($35m budget) and less star-packed Mojin: The Lost Legend grossed $255m in the same release period last year

And, as previously stated, people in China didn’t seem to like Great Wall all that much.

From ChinaFilmInsider:

Moviegoers from Thursday’s advanced screenings have already loudly mocked the film online — Douban currently sits at an awful 5.8/10 — targeting their vitriol at the “fresh meats” (Lu Han and Wang Junkai of the boyband TFBOYS) and their complete lack of onscreen presence.

Most netizen hatred and critical consensus seems to be aimed squarely at young Jing Tian, a 28-year-old actress whose biggest credit to date was the critically panned From Vegas to Macau 3. Jing reportedly commands more onscreen time than her Chinese counterparts combined but is unable to hold her own against Damon. Adding fuel to the fire, Jing is set to star in two future Legendary productions — Kong: Skull Island and Pacific Rim: Uprising — giving netizens plenty of fodder to speculate on Jing’s powerful connections.

The film’s director Zhang Yimou is revered in China for having kickstarted the age of the Chinese action blockbuster with Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004) and Curse of the Golden Flower (2006), and for directing the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games. However, his critical reputation has waned in recent years, and some Chinese audiences seemed to view Great Wall as being another entry in his downward spiral. One influential reviewer lamented “Zhang Yimou has died” the day Great Wall came out, prompting an angry letter from the film’s production company demanding an apology. While retracting his overly harsh rhetoric, the reviewer explained, “I just feel that Zhang’s art career is almost coming to an end,” pointing to Great Wall’s meager sub-6.0 averages on IMDB and Douban respectively as back-up.

The Global Times, a Chinese state-backed newspaper, concluded, “Bearing the various negative reactions in mind, I saw the film on its second day of release. To be honest, I can’t say The Great Wall is a splendid work that everyone must see, but it is not that bad either. It is, in my opinion, a film that has been carefully tailored to be a blockbuster popcorn flick.” They also acknowledged an uneasiness with seeing a beloved cultural landmark like The Great Wall being forced to now share its name with a mindless action movie. Nowhere in their review, though, did they reference Matt Damon and Hollywood’s white savior problem.

In a separate Global Times article, Chen Changye, editor-in-chief of the Chinese film blog Yiyuguancha, had a very pragmatic reaction to Damon’s presence in the film:

The US film industry is more concerned about [whitewashing] because they were one of the earliest to launch affirmative action and due to the country’s strong diversity […] Choosing Hollywood movie stars in a production like this is an inevitable business decision. If Chinese movie producers want to sell a film in Hollywood and around the world, they have to bring in Caucasian actors and actresses to play roles meant for Asians or create Caucasian roles in the film for them. This is not discrimination, it’s just business. Chinese stars, such as Zhang Ziyi and Jing Tian, are not as globally-influential as Hollywood celebrities yet. This is the reality.

But now I need to stop and acknowledge that I’m just some dude in the American Midwest. I’ve never been to China, and can no more speak to their opinions than Matt Damon can save them from monsters. Plus, I’m not 100% sure if The Global Times is considered a trusted source or a propaganda machine (or both). However, it does seem apparent that the outrage we’ve expressed about The Great Wall here has not been as widely replicated over there.

Perhaps we’re simply more attuned to it than somewhere like China due to our diversity and history of affirmative action, as Chen argued, as well as our collective embarrassment over a cultural legacy which includes this:

And maybe we’ve all never forgiven Matt Damon for this:

What do you think? Does it matter that Chinese audiences didn’t seem to mind Matt Damon’s presence in The Great Wall as much as us? And are you someone living in China right now and totally disagree with my assessment? Oh, you are. Really? Awesome! Let me know in the comments.

Source: ChinaFilmInsider, The Global Times

I mostly wish that people would stop using The Last Samurai as an example for the white saviour syndrome, since it is very arguable if the movie actually falls into this trope. The idea of the movie is more that the white character serves as an audience surrogate in order to explain the concept behind Samurai culture. Remember, there isn’t much saving going on in this movie, the Samurai all die for their cause, and the role of the Cruise character is mostly to be all “I don’t get you” and then getting a smack down when the ideas and concept behind this way of live is explained to him. There is one scene at the very end which can be used to argue this point and the title is very unfortunate because everyone seems to assume that Cruise is supposed to be The Last Samurai when actually he is just witnessing the fate of the last Samurai, but all in all, it isn’t a particularly good example for the white saviour syndrome. It would be better to stick with Dancing with Wolves or Avatar to make that point.

Concerning The Great Wall…I think there is something we have to consider: Both Japan and China have their own movie industry. They get a number of movies every year in which the heroes are not white at all. In addition, Japan is a very isolated country overall. It is kind of natural that people who present the majority in their own country and do get a number of movies which represent them every year would react differently to The Great Wall than Asian-American people, who are part of a minority in their country, and don’t really have access to Asian movie productions due to Americans having the tendency to snub everything which isn’t made by Hollywood – or just remake it. I think what really needs to change is the attitude of the US audience towards foreign language movies. Or, to put it differently: They should just dub successful foreign movies and release them like every other movies in their theatres. That would solve a lot of the representation problem with the added benefit that Americans would finally get some new perspective on things.

“I mostly wish that people would stop using The Last Samurai as an example for the white saviour syndrome, since it is very arguable if the movie actually falls into this trope”

You make a fair argument. I’d guess that a surprisingly high number of people who use Last Samurai as a white savior example have never actually seen the movie. It is on Netflix now, though. So there’s that.

” I think what really needs to change is the attitude of the US audience towards foreign language movies. Or, to put it differently: They should just dub successful foreign movies and release them like every other movies in their theatres. That would solve a lot of the representation problem with the added benefit that Americans would finally get some new perspective on things.”

What’s interesting there is I have now seen or heard multiple stories about there being a bit of a demand in China right now for Asian-American actors, the type who could come in and speak both English and Mandarin and possibly serve as some kind of bridge to other markets, as in “Here’s so and so from some American TV show you might now, and he’s in our Chinese movie now.”

well, that was why Matt Damon was in the Wall, right? We will have to wait and see how that develops…