The western, which used to be as common in Hollywood as superhero movies are now, enjoyed a surprising revival in popularity in the late 1980s into the 90s. The genre, of course, fizzled out again and faded from memory. Film financiers didn’t see a profit in it and audiences lost their appetite for it. However, for a good 6 years westerns were cool again. They won Oscars, starred some of the biggest names in Hollywood, and inspired Bon Jovi to sing about riding on steel horses and being shot down in a blaze of glory.

It all started with Young Guns, the Brat Pack western which celebrates its 30th anniversary this month and is newly available on Netflix. The passion project of a 27-year-old screenwriting wunderkind and largely financed through money from Subaru dealerships, this Billy the Kid movie has always failed to garner much critical respect, yet it remains one of my favorite westerns.

The following is the story of how Young Guns got made and how it entered into steady rotation on the TV in my childhood home.

When Charlie Sheen won the Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Comedy for Spin City in 2002, he kicked off his acceptance speech by declaring, “This is so surreal. This is like a sober acid trip.” Adding to the surreality of the evening was Kiefer Sutherland later winning Best Actor in a Drama for 24. He instantly joked, “I now know what Charlie meant. I just lost complete feeling in my lower half.”

Once the princes of Hollywood, they’d each suffered through various personal and career misfortunes throughout the 90s before finding salvation on TV in the early 2000s. Now, here they were having their comeback projects officially anointed on the same night. This connection was not lost on those in the media who made sure to note this rather peculiar twist of fate in their coverage of the show.

All I could think, however, was this: Holy shit, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association just awarded two-sixths of the cast of Young Guns! Is Lou Diamond Phillips also going to win something? Where’s Emilio Estevez? And don’t leave Dermot Mulroney and Casey Siemaszko out of the party!

Watching Young Guns as a kid

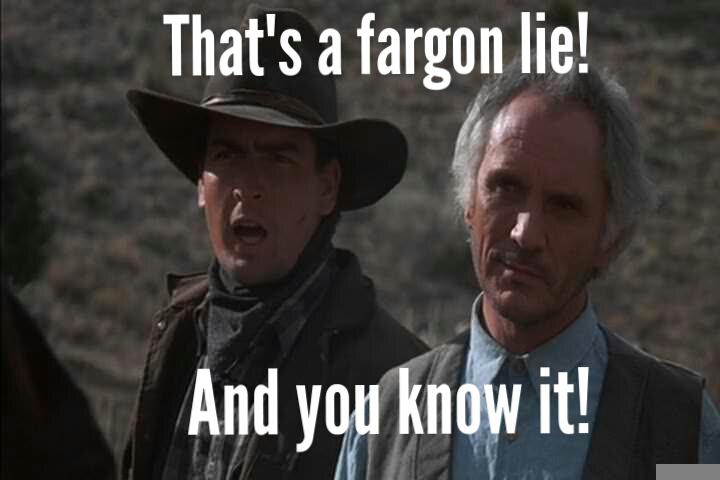

That’s the connection I immediately made because, well, Young Guns was a big part of my childhood. It’s the movie I watched ad nauseam with my older brothers, our fascination with the Old West merging perfectly with our glee in mocking Charlie Sheen, who makes an art form out of hilariously over pronouncing the name Billy (his version: “Billay”) and old-timey curse word “fargon” throughout the film. Reportedly, the other actors in the cast also teased Sheen about that, but the days when Sheen’s biggest sin was overcompensating on the set of a western seem so quaint now.

However, if mockable Sheenisms were all we needed for movies to bond over I could very well be writing this article about something like The Chase or Terminal Velocity. Young Guns took special root in my childhood because it stood out. I’d never seen anything like it before nor had I seen so many trendy actors all in the same movie together (I obviously hadn’t seen The Outsiders yet). It also resonated thematically. As the Los Angeles Times noted in its review of the film, it’s “a paean to teen-age camaraderie and loyalty.”

After watching their father figure (a perfectly dignified Terence Stamp) ruthlessly gunned down by a posse commissioned by a rival businessman, Billy the Kid (Emilio Estevez) and his friends (Sheen, Sutherland, Phillips, Mulroney, Siemaszko) set out for justice as newly deputized regulators but end up settling for cold-blooded revenge. The adults in the room (mostly Terry O’Quinn) consistently tell them to step back in line, yet they can’t stop themselves from pursuing what they think to be right (or simply following Billy’s thrill-seeking lead). By the time of the final shootout, they are badly outnumbered and outgunned, with little more than their grit and ironclad bond to lean on.

Billy the Kid: His Actual History

More so than most prior Billy the Kid movies, the story is based in history. At the age of 18, Billy, born Henry McCarty, became a central figure in the Lincoln County Wars, which was really an escalating series of skirmishes between merchants competing for government contracts to supply an Army fort and an Indian reservation in New Mexico. The 24-year-old John Tunstall (not at all the father figure he’s always depicted as in film) thought he could fairly compete with the monopoly held by James Dolan and Lawrence Murphy (played in the film with sneering glee by Jack Palance). He thought wrong, obviously, and his murder set off a series of revenge killings, culminating in a five-day siege known as the Battle of Lincoln.

Billy’s genuinely stunning escape from that Battle fed his legend but also further motivated authorities to hunt him down. Rather than run for the border or flee for another state, he foolishly stuck around in New Mexico, watching most of his fellow Regulators mowed down before he himself was shot dead by Pat Garrett in 1881. He was only 21-years-old.

Billy the Kid: His Hollywood History Prior to Young Guns

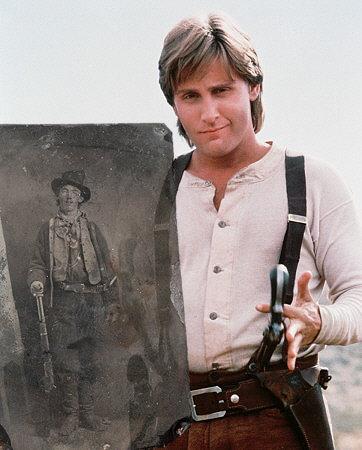

By 1988, John Fusco, who grew up collecting material and works of research on Billy the Kid, knew all of this backwards and forward. “I was about 10 years old when I saw my first photograph of Billy the Kid,” he told a Los Angeles Times reporter during a Young Guns set visit. “This little 5-foot-4, rodent-faced character (in the photo) just didn’t correspond with the legend of Billy, the noble bandit dressed in black–Johnny Mack Brown, Robert Taylor.”

Indeed, in the western’s heyday playing Billy the Kid was a rite of passage for certain actors. Roy Rogers, Audie Murphy, Paul Newman, and Kris Kristofferson all got their turn. Jack Beutel played him in Howard Hughes’ infamous The Outlaw, where just about everyone, Beutel included, was upstated by Jane Russell’s cleavage. However, historical fielty often gave way to pulpy mythmaking and, eventually, cartoonish ridicule, as in 1966’s Billy the Kid Versus Dracula.

The only film version of Billy which Fusco recognized as being remotely close to the actual historical figure was Michael J. Pollard’s turn in 1972’s Dirty Little Billy. Fusco considered Billy’s cause to be just, but his actions were often anything but, clearly the killing spree of a psychopath. Pollard, appropriately, played him as “a drooling, stumbling moron,” far removed from the figure of legend. However, whereas most other Billy the Kid movies at least paid some lip service to the historical details – as exaggerated as they might have been – of the man’s life, Dirty Little Billy plunged into pure fiction. To Fusco, this was deeply disappointing, reinforcing the need for a definitive Billy the Kid movie.

Young Guns finally takes shape

Fusco wasn’t initially convinced he was the man to write that movie. Given the wealth of research he’d already collected, he briefly considered simply writing a novel about Billy. However, after striking it big as a screenwriter with 1986’s Crossroads, a Robert Johnson biopic he actually just wrote as an assignment in a masters class at New York University’s Tisch School for the Arts, he decided his next project would be to tackle the Lincoln County War. Three months of research and one month of writing later, Fusco had his first draft of Young Guns.

In the script, as in the movie, Billy rides “for all the right reasons.” As Fusco told the LA Times, “It’s very easy to see why he became a hero–he had a lot of support from the farmers who were under Murphy’s heel. But it was the way he went about it. He was monomaniacal about friendships, about justice. He killed anyone remotely involved or whom he suspected of being involved (with the Murphy faction), and he killed in a very crafty, unheroic way.”

That, of course, fed his dime store novel notoriety, and Young Guns doesn’t shy away from depicting the joy Billy received from killing or the ingenuity he put into it. The following scene, which has no real bearing on the plot but was just too fun to be left out, is a perfect example of this, especially since Billy apparently really did kill someone like this, if not in this exact detail:

Paul Newman had played Billy (in 1958’s The Left-Handed Gun) as a mixed up youth with a one-way ticket to an early grave. Clearly, Estevez took it much further. As the LA Times noted in its review, “A notably dirty fighter, [Estevez’s Billy] giggles delightedly after gunning someone down, whoops with near-carnal delight when he finds himself and his gang besieged by several posses and the U.S. Cavalry. He’s a baby-faced Nietzschean warrior.”

Not that Estevez was completely comfortable with that. “It was difficult for me to accept killing another man on screen. I wrestled with that for a while. Then in doing the research, in learning more about Billy, the homicides became justifiable and easier for me to do on screen,” he told the Times while shooting the movie. “Killing, for him, was very Zen–I don’t know how else to describe it. He was fascinated by how a man could just change (shift) his weight and change the course of history.”

This, from the get-go, was Fusco’s goal. He wanted to find “the real Billy.”

Hollywood says no

Before Fusco could find his Billy, though, he had to first find someone willing to buy his script. That turned out to be harder than he expected. The newly created Tri-Star Pictures, which had a deal with Fusco based off Crossroads, passed.

By that point, Fusco’s script had already attracted a director, Christopher Cain (Dean Cain’s adopted dad), who had just directed Emilio Estevez in 1985’s S.E. Hinton adaptation That Was Then…This is Now. He was completely sold on Fusco’s script by page 20, but they kept having doors shut in their face all around town. The logic was much the same as it is now for anyone looking to make a western: where’s the profit?

“Remember Heaven’s Gate,” they’d all say. After all, the 80s started off with a western so monumentally self-indulgent and impossible to decipher that it destroyed a director’s career and drove a film studio out of business. Heaven’s Gate, which only earned back 6% of its $44m budget, nearly killed the genre. Hollywood didn’t release another western of note until five years later when Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider and Lawrence Kasdan’s Silverado arrived within one month of another. They each prospered at the box office, but only Pale Rider did so in cost-efficient way, grossing $41m while costing just $6.9m. Silverado, by comparison, made around $8m less than that while costing three if not four times as much to make.

The model was clear: if Young Guns was going to get made it would have be at a reduced cost. Cain and Fusco heard the same story everywhere they went: “‘Oh, it’s a great script–it’s a Western. Oh, it’s exciting–we don’t want to do it.’”

Independence financing to the rescue

So, Cain turned to producer Joe Roth, with whom he’d previously worked on the films Stone Boy and Where the River Runs Black. Through his Morgan Creek Productions, Roth had an “arrangement” which would be perfect for them.

The details, as summarized in the Times, are as follows: “James Robinson, Roth’s Baltimore-based, Subaru-distributorship-rich partner in Morgan Creek Productions, fully financed the film’s production and, in a further bid for autonomy, covered its advertising costs.”

The Young Guns budget came in just north of $11 million, at least half the size of Silverado’s three years earlier, with the cost-cutting coming largely from the choice to film with a non-union crew. The actors were all paid their market rate, but much of the below-the-line work was done by the locals in Cerillos, New Mexico, “a backwater of 300 souls in the red-sand hills” south of Sante Fe. Production designer Jane Musky, who would later work on classics like When Harry Met Sally and Ghost and most recently earned a credit on Netflix’s surprise hit rom-com Set It Up, took over the town and recreated 1878 Lincoln, NM.

To appease the natives, they put them to work, hiring 21 local horse wranglers, 10 local women for the costume department, and 50 local day laborers to assist in set construction, paying the latter $350 for a 32 1/2-hour workweek. 75% of all the horses in the movie were also sourced locally. Some of the citizens complained since the community was never approached as a whole but instead individually; others were simply happy to have the work.

The appeal of working on the film for the cast was equally pragmatic: “Because it’s a Western and how often do you get the opportunity to do one?”

Also, for Estevez, Sheen, Phillips, and Sutherland it was fun to simply be a part of an ensemble and thus not have to carry so much the movie. Sheen, for example, though only 22-years-old had already starred in Platoon (1986) and Wall Street (1987), and Phillips was fresh off of his star-making turn as Ritchie Valens in La Bamba (1987). Sutherland had already played the villains in Stand By Me (1986) and The Lost Boys (1987). Siemaszko, the oldest of the group at 27, was more accustomed to such ensemble work, having played henchman-like roles in Back to the Future and alongside Sutherland’s iconic “Ace” in Stand By Me. Mulroney, by comparison, was the relative newcomer with very few credits.

Any of the ego trips you’d expect from such young, competitive talent never really materialized. “The fact that we are all really very different types and would never be up for the same role reduces any sense of competition between us,” explained Phillips.

The collection of such young talent was partially a reflection of the real Regulators, who were generally young vagrants taken in by Tunstall and given education and shelter in exchange for providing security, but it was also part of Fusco’s strategy to get the film made. Put that many names into a project and surely it will awaken something in somebody’s marketing department, he hoped. It certainly awakened something in Cerillos.

“Literally, the girls that were leaving would pass the ones coming in” – Love and Sex in Cerillos

During filming, local adolescent girls cued up to either land jobs as $40-a-day extras or to simply gawk at the hot guys from afar. Many a teenage heart was crushed when word spread that both Sutherland and Phillips were already married. The other guys in the cast, on the other hand, well…

“It wasn’t as bad as on Young Guns [a year earlier],” Charlie Sheen told Sports Illustrated in an oral history about Major League. As per his tiger blood ways, Sheen had a steady rotation of woman coming to and leaving the set, but since it was a physically demanding sports movie he kept his womanizing to a minimum – by his standards at least. He suffered no such limitations on Young Guns.

“We made that one in Santa Fe, and you would fly into Albuquerque and drive to Santa Fe on this two-lane highway. Literally, the girls that were leaving would pass the ones coming in.”

That kind of reputation seemed to follow Young Guns and doom it to forever be dismissed as a somehow lesser-than western. In her rather backhanded New York Times review, Janet Maslin argued, “The western Young Guns is less like a real movie than an extended photo opportunity for its trendy young stars.” Time quipped in its review, “A grownup could die in this wasteland.” In 2013, Mary Lea Brandy, the Chief Curator of the Department of Film and Video at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, co-authored a definitive history of the western film, and she failed to even acknowledge Young Guns’ existence, highlighting instead the 1989 Lonesome Dove TV mini-series.

The release and legacy

Upon release, however, Young Guns wasn’t exactly savaged by critics. It was mostly offered backhanded compliments (Roger Ebert, for one, was an unabashed fan). It turned into a surprise late summer hit for 20th Century Fox, capping a resurgent couple of months for the studio after Big and Die Hard. When the dust settled, Young Guns even outgrossed Pale Rider by around $3m. Its final gross, $44m, converts to $103m at current ticket prices, which is more than the recent Denzel Washington/Chris Pratt Magnificent Seven remake.

The western was profitable again.

Within a year, Joe Roth transferred from Morgan Creek to become the new head of Fox’s film division. One of his first projects? Young Guns II, of course. John Fusco agreed to return as screenwriter. Christopher Cain was replaced by New Zealand’s own Geoff Murphy.

Released in 1990, the sequel upped the sexy factor by adding Christian Slater to the Teen Beat cast and also came with a Bon Jovi-penned soundtrack. The fact that it was far less historically accurate or critically appreciated than its predecessor didn’t much matter. It again grossed $44m

Fusco had succeeded. The world finally knew the version of Billy he always saw in his head.

The Western Retakes the Spotlight

Meanwhile, in Young Guns’ wake Marty McFly traveled back to the Old West to save Doc. Dances with Wolves and Unforgiven each took home significant Oscars and box office glory. Jack Palance, just 4 years removed from his turn in Young Guns, won an Oscar for the revisionist comedy western City Slickers. There were not one but two competing Wyatt Earp movies (the superior of the two being Tombstone, of course). The world’s most handsome man, Mel Gibson, made river boat poker games seem like the epitome of cool in 1994’s Maverick. A year later, the world’s sexiest actress, Sharon Stone, took a stab at a feminist western with The Quick and the Dead, and Johnny Depp found art-house acclaim with Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man.

Ok. Admittedly, by the time The Quick and the Dead arrived the western had again faded from popularity. The concurrent financial failure of Dead Man and of the all-female western Bad Girls a year earlier was further indication of that. However, at least by that point kids around the world had been reminded of the existence of cowboys and Indians.

And that started with Young Guns.

Does Young Guns Still Hold Up?

When watched today, Young Guns occasionally betrays its age, particularly in the form of co-composers Anthony Marinelli and Brian Banks’ rock-leaning score, which was added last-minute – and it shows! – after a completed score from James Horner was thrown out. Furthermore, Christopher Cain’s use of grainy footage and slow-motion during the shoot-out finale seems more puzzling than thrilling. However, as a tale of a just cause giving way to senseless violence and a snapshot of a group of actors just entering their charismatic prime Young Guns holds up. Morgan Creek has been kicking the tires on a possible remake as of late, but it’s hard to beat the original.

What about you? What are your memories of Young Guns? Are you troubled by that sub-plot between Sutherland and Palance’s Chinese girl? Struggle to enjoy anything Sheen-related these days due to his, um, “troubles”? Have you always considered Young Guns to be little more than harmless late 80s fluff? Or are you still wondering if we’re all just stuck in the Young Guns spirit world? Let me know in the comments.

My next film anniversary article will come later this month when Needful Things turns 25. You can also read my reflection on Running Man here.

Emilio Estevez was the greatest. That is all.

Completely agree. That is all 🙂

I was a teenager when I saw his so I was Delfina one of the young women who was simply gawking at all the pretty men. But it was an enjoyable enough movie, and I liked it just fine.

I’ve watched it several times over the years, and I really do feel the film is underrated. I loved the cinematography, which is gritty and gorgeous, and a rival for a lot of westerns produced today. The dialogue could’ve used more polish but I still don’t find anything particularly wrong with the acting, which is just fine, and I’m unperturbed by the Chinese girl storyline. I know enough about that time period to know that’s not out of keeping with how things happened back then, (and Doc gets to have a happy ending due to her introduction).

You probably couldn’t get me to watch anything Sheen made in the 90s, but his presence in this movie doesn’t bother me, probably for nostalgic reasons, and his reputation hadn’t been destroyed yet. Also it was one of the first movies I enjoyed that had both Sheens in it (Sheen and Estevez).

“I really do feel the film is underrated”

I actually went to the library to sift through some more academic texts about the western genre and I was stunned to find not a single one of them even acknowledged Young Gun’s existence. I mean, come on, I know it’s the Brat Pack on horseback, and the music is seriously dated but it’s a damn good movie, one that at least deserves to be mentioned as a (if not artistically than definitely financially) important film of its era.

“The dialogue could’ve used more polish but I still don’t find anything particularly wrong with the acting, which is just fine, and I’m unperturbed by the Chinese girl storyline”

I re-watched the movie on Netflix before writing the piece, and I had actually forgotten all about that storyline. It struck me as something which might give 2018 audiences pause, considering how little agency the girl has in the scenario, but, as you said, it’s sadly accurate to the era.

“Doc gets to have a happy ending due to her introduction”

The funny thing to me is Young Guns gives Doc this great happy ending and then kills him in Young Guns 2. Same goes for Chavez. It was so inconvenient for them that neither of those people played any part in the Billy the Kid story after the Battle of Lincoln. Doc had a shitton of kids and lived a long life. Chavez went off and became a cop somewhere. That’s what really happened, but how do you make a Young Guns 2 without Kiefer and Lou Diamond Phillips? The answer is you don’t.

“You probably couldn’t get me to watch anything Sheen made in the 90s”

Ditto. Well….maybe the Hot Shots movies.

“Also it was one of the first movies I enjoyed that had both Sheens in it (Sheen and Estevez).”

Impromptu ranking of Estevez/Sheen movies I’ve seen:

1. Young Guns

2. Men at Work

3. Rated X

Oh, wow! No wonder I’ve never seen any of their other movies together. I did watch Charlie and Martin in some military movie though, called Cadence (although I know they starred in other stuff together, I haven’t watched any of those).

“Oh, wow! No wonder I’ve never seen any of their other movies together.”

I’m pretty sure they’ve cameoed in eachother’s movies. Like, some sites say Charlie is in Loaded Weapon 1 with Emilio, but I don’t remember it. However, in terms of full movies in which they are basically equal co-stars those are the only three I know of. Young Guns is easily the best of the bunch.

“I did watch Charlie and Martin in some military movie though, called Cadence (although I know they starred in other stuff together, I haven’t watched any of those).”

The movies they made with their dad is another matter. It seems to me that, basically, when Charlie was at his lowest Martin did a series of direct-to-video movies with him to sort of help him get back on his feet and get his shit together. Then, when Charlie went off the deep end Emilio and Martin made a movie together that was so clearly about Charlie’s self-destruction – the plot involves a father (Martin) mourning the premature death of his adult son (Emilio). It’s called The Way. Never seen it, unfortunately.

I loved reading this so much. I LOVE YG’s 1 & 2. I watched them both a million times. Part 2 was more my favorite because of the soundtrack.

Thanks for reading and commenting. I’m glad you enjoyed the article. I’m in the same boat re: watching them both a million times, and any conversation of YG2 does usually begin with the soundtrack. Shot down in a blaze of glory, after all. “Wanted: Dead or Alive” is the one that always plays on the radio and populates karaoke bars, but “Blaze of Glory” is a pretty worthy sister song to its more famous predecessor.

Movies and music have a way of becoming permanently attached to memories. My freshman year in college, I was pretty sheltered and naive. I became friends with a guy I met in class and he invited me to a party. Everyone got wasted and I noticed all of the police patrols. I was petrified of getting arrested for drinking underage. I asked my friend how we would get by all the police.

He says, “We’re in the spirit world, a-hole! They can’t see us!”

Heck, my brothers and I still use “spirit world” as an in-joke for moments like that. Ah, the odd ways some films stick with us.

Young guns is an all time favorite of mine, the violence, the look and the feel of the movie all come together for a pleasant veiwing experience. I was born in 91 and watched this movie all threw my child hood and even watching it today. A remake is unnecessary but if done right I’d love to see it.

Regulators, mount up! I love that this movie was a favorite of yours when you were a kid. Obviously, the same goes for me, and other than the Mega Man musical score I think the film holds up fairly well today.

In the time since I wrote this article, I haven’t seen any update about that Young Guns remake. In this current era of Hollywood, it’s entirely common to hear about a remake and then flash-forward a couple years later and have no idea if the project is still happening or if it died in obscurity. That’s generally always been true of Hollywood’s development cycle, but since there are just so many remakes/sequels/revivals/requels these days it’s a lot harder to keep track of it all. I do wonder if Young Guns might feel like a non-starter to a lot of film financiers since westerns usually struggle to sell tickets overseas these days.

This exact sentiment sent me down a rabbit hole searching for other like minded individuals. Certainly there were some non-pretentious ‘outside of the box’ movie lovers who realized after all these years YG1+2 are two of the most entertaining western flicks ever created. Emilio Estives effortlessly owns Billy “the Kid’s” swagger and it feel’s like an immersive, dangerous and expansive world for our fun loving young psychopath’s misadventures. This was not a mistake nor is this bad cinema, it’s several engaging characters including a pitch perfect second film appearance by the criminally underrated and somehow forgotten (perhaps part of the reason for my misanthropy? True Romance anyone? Amiright?) Christian Slater. Hell, just the banter between Slater and Emilio about who ran the gang was worth ten “Wyatt Earp’s” and 1/4 of a “Tombstone”( love that one too). Please understand, I love storytelling, I’ve read Hemingway (yay) and Faulkner (puke), I’m obsessed with Anime, I love comic books, I straight up know my shit when it comes to great storytelling with exciting characters in multiple mediums, and I love ‘Unforgiven’ and can appreciate the difference in depth concerning the depiction of the human condition, but that has not historically been, nor should it ever be, what attracts people to a story. If it is entertaining it has done its job, and dammit I love hearing Billy’s infectious laugh, his bond with a super cool whore, his sense of camaraderie “I just know to stick (together)” and “pal’s” are endearing qualities added to a charismatic young serial killer, what in hell is not to love?? You can keep another boring, subtle “woke” Kristen Stewart performance, these actors were having a blast and ALL were invited to join in. This level of fun in film is rarely seen anymore and it’s a damn shame. “I shall finish the game, Doc”… Shit I love that line.

The horses looked like they were treated so rough—it makes one wonder if anyone was looking out for them during the shoot, or if they were just sacrificed to get the “authentic” shot…if they were filming outside of the law, i’m guessing that went for the anti-cruelty laws as well. It makes me sad to see them getting jerked around so.

there is a disclaimer in part 2 that says none of the animals were harmed and union stuff. i’m sure it’s in part 1 also

I love both movies though I will say the rock music is not bad in the original but i just heard parts of what James Horner wanted to do and I like that better. part 2 the music is perfect though

I thought journalists were required to do their research in order to avoid writing falsehoods. Bon Jovi’s “Wanted” was written in 1986, released that year on the album Slippery When Wet. To further clarify, “Blaze of Glory” was an entirely different song, released on a Jon Bon Jovi solo album. Lastly, Young Guns did not inspire “Wanted”—it was released two years before YG, which was released in 1988. Amazing what passes for journalism these days. smh